Key points:

- Amortization is the process of paying back what you’ve borrowed, usually in periodic installments (e.g., monthly mortgage payments).

- When the mortgage balance reaches $0, the loan is fully amortized.

- Lenders calculate an amortization schedule to determine how much of each monthly payment should go toward the principal (your loan balance), and how much toward interest.

Amortization is the process of paying off a loan. A mortgage is fully amortized when its balance reaches $0. Lenders create an amortization schedule to map out how the homeowner will fully pay off both the amount they’ve borrowed and the interest on it by the end of the loan term. That usually means paying a pretty hefty amount of interest each month, especially in the beginning.

If you have a mortgage, you have a monthly payment to make to your lender. Most homeowners choose a fixed-rate loan, which means that payment doesn’t change over the life of the loan. But the way that monthly sum gets allocated does.

Let’s say you have a monthly payment of $2,200, and $350 of that goes towards property taxes and insurance. The remaining $1,850 goes toward paying down your mortgage balance, right?

Wrong.

Before any money goes toward reducing what you owe your lender, you need to pay off the interest that’s built up over the last month.

In the beginning of your mortgage, the majority of your monthly payment goes toward that interest. As you gradually pay down your balance, though, less interest accrues between each month. Eventually, you’ll reach the point where more of what you hand over each month goes toward your balance than your interest.

Fortunately, you don’t have to crunch the numbers every month to figure out how much needs to go toward interest. You also don’t need to calculate how much to hand over to make sure you finish paying off your home loan by the end of its term (usually, 30 or 15 years). Your lender does this for you. They keep track of this through what they call an amortization schedule.

Defining amortization and related words

To put it as simply as possible:

Amortization is the process of paying off a debt, usually through periodic payments, to zero out the loan balance.

To make this conversation easier, it helps to define some more terms that relate to amortization, too. When you borrow a sum of money from a mortgage lender, they call that balance your principal. On a $425,000 loan, for example, the principal is $425,000. As you pay off your loan, that principal shrinks.

When lenders talk about amortization, they’re referring to how payments toward both your principal and interest — they call this P&I — pay back what you’ve borrowed over the loan term.

And that leads us to one final term to define: term. When lenders say that, they don’t mean a word, or even a condition of a contract. Instead, a loan term is the amount of time you have to pay back what you borrowed. On a 30-year mortgage, then, the term is 30 years.

Let’s recap:

- Amortization: The process of paying back what you’ve borrowed over time until your loan balance reaches $0, at which point the loan is fully amortized.

- Principal: The loan balance, which starts at whatever amount you initially borrow and gets smaller as you make payments toward that balance.

- P&I: Short for principal and interest, these are the two categories lenders calculate when determining the monthly payment required to amortize your loan.

- Term: The amount of time you have to fully amortize the loan.

In a world where interest didn’t exist, amortization would be simple. You could fully amortize (i.e., pay off) a $100 loan by making 10 monthly payments of $10.

Even with larger sums, this would still be simple. To fully amortize $425,000 of interest-free debt in 30 years (360 months), you would pay $1,180.55 a month (425,000 / 360).

Even if you got a mortgage when interest rates were at record lows during the pandemic, that monthly payment might sound low to you. That’s because interest adds a notable amount each month. Your amortization schedule breaks down your P&I payment, and shows you how much of your monthly dues go toward interest.

Using your amortization schedule to understand how your mortgage payments get applied

There’s a world in which you never really need to care about amortization. As long as you trust your lender and make the monthly payments they require, you should be on track to pay off (amortize) your mortgage by the end of its term.

But there might come a time when you look at your monthly payment breakdown — and have a moment of panic. Early in the amortization schedule, a shocking amount of your monthly payment goes toward interest.

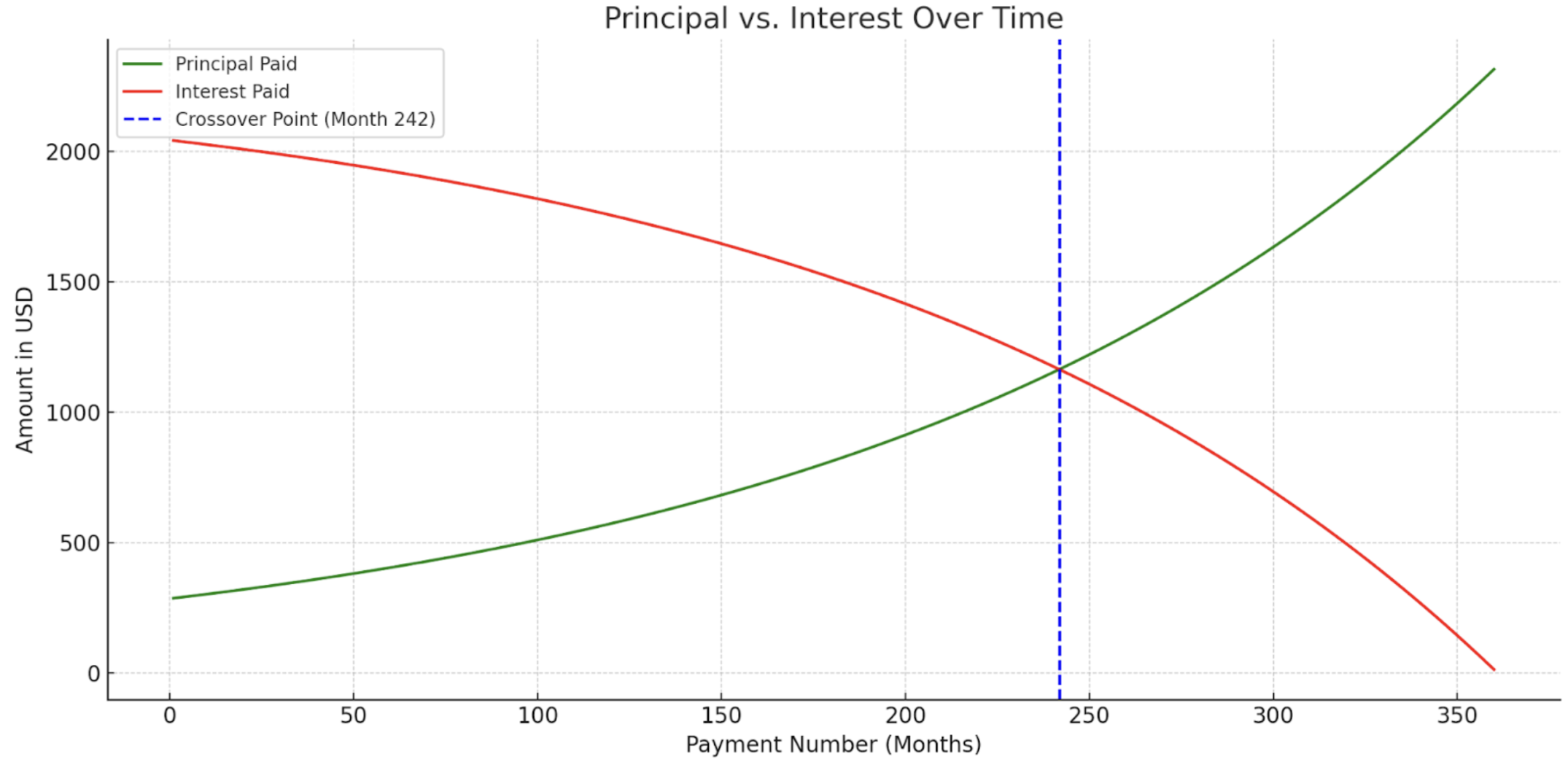

The bigger your loan balance is, the more interest that accrues between each monthly payment. In the early days of your mortgage, then, you’re going to pay a pretty hefty amount in interest. With interest rates where they are right now, most homebuyers will make mortgage payments for more than two decades before these scales start to tip.

Let’s take, for example, a homeowner who buys right now, taking out a 30-year $350,000 mortgage with a fixed interest rate of 7%.

Here’s a look at the first year of that new homeowner’s amortization schedule:

Clearly, in the beginning, the amortization schedule dictates that the majority of each monthly P&I payment goes toward interest. Eventually, that will change — but that takes a while. For this specific example, the principal payment won’t be bigger than the interest payment until 20 years and two months into the loan.

When you get your amortization schedule and see how much goes toward interest, don’t be shocked. That’s normal.

That large amount of interest you’re paying isn’t all bad news, either. You can deduct mortgage interest on your taxes for up to $750,000 of debt.

A word on adjustable-rate mortgages

The example we just explored applies to a fixed-rate mortgage. If you get an adjustable-rate mortgage (ARM), your interest rate can — as the name implies — adjust. As a result, the payments you’ll need to make to amortize your loan will change, too.

Finding ways to pay less in interest

Now that you have a better feel for amortization, you’re probably realizing why getting the best mortgage interest rate you can is so important.

Understanding the current rate environment (our Rates.Now rate tables help there) and comparing offers from lenders helps you confirm you’re getting the lowest rate possible. And even a slightly lower rate can save you thousands of dollars as you amortize your mortgage through the years.